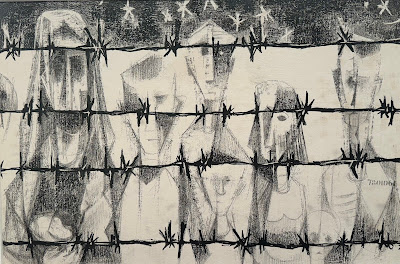

These hollow-eyed women could be the victims of any war.

That's the point of "The Parade," a powerful suite of work by

Si Lewen, a Polish Jew born shortly after World War I who fled the Nazis with his parents to New York where an anti-Semitic cop assaulted him in Central Park. He recovered from an attempt to poison himself shortly afterward in 1936, eventually enlisting in the US Army where, as a member of the

Ritchie Boys, he witnessed the liberation of

Buchenwald, which precipitated another mental breakdown.

Lewen went on to produce "The Parade," one of the 20th century's great indictments of nationalism and war, largely under the radar because of the medium he chose, a precursor to today's graphic novels.

Lewen traces the phases of war in 63 black and white drawings, without a word. Excited crowds waving flags line the streets in the first surge of patriotism prior to the commencement of battle. The recurring dog seems to function as a witness.

Goose-stepping soldiers hold their rifles at the same angle as their legs.

Lewen's approach reminds me a little of Civil War, a controversial film directed by Alex Garland. These soldiers lack ideology, too. They could be Israelis or Palestinians.

A parent holds up a child with a flag in support of whatever the cause, inculcating a new generation with hatred.

I can't tell if this child is gazing into a parent's eyes. Or a nun's. Or death's.

Despite everything he saw and endured, Lewen kept his sense of humor. In this scene, which recalls the absurdity of the war in Viet Nam for my generation, medical personnel examine conscripts to ensure they're healthy enough to kill people.

Basic training, just like in Full Metal Jacket, an equally powerful anti-war film by Stanley Kubrick who also directed Paths of Glory, which examines the inhumanities of military decision-making.

The high velocity of civilian death is inevitable and propulsively illustrated.

Lewen had to flee home three times during his life. First, as a toddler, after his family's home in Lublin was burned to the ground in a progrom, then as a 13-year-old to avoid increasing anti-Semitism in Berlin and finally, a miraculous escape to America in 1935, when Jews weren't permitted to immigrate.

Battlefield horrors vary.

These people are the lucky ones. If you're injured, at least you're alive.

"The Parade" comes full circle with the veterans' return except this time a parent shields their child from the hoopla.

In 1951, when Lewin first exhibited his drawings in New York,

Albert Einstein, then a Princeton professor, took notice and wrote him a fan letter:

I find your work "The Parade" very impressive from a purely artistic standpoint. Furthermore, I find it a real merit to counteract the tendencies towards war through the medium of art. Nothing can equal the psychological effect of real art—neither factual descriptions nor intellectual discussion.

It has often been said that art should not be used to serve any political or otherwise practical goals. But I could never agree with this point of view. It is true that it is utterly wrong and disgusting if some direction of thought and expression is forced upon the artist from the outside. But strong emotional tendencies of the artist himself have often given birth to truly great works of art. One has only to think of Swift's Gulliver's Travels and Daumier's immortal drawings directed against the corruption in French politics of his time. Our time needs you and your work!

Lewen died in 2016, at the age of 98. It's doubtful that the decades-long peace dividend Europe experienced after the fall of the Soviet Union fooled him.

No comments:

Post a Comment