En route to South Boston via Amtrak, I stopped overnight in New London. Randy picked me up at the station in his new Volvo. While gabbing about our new electric vehicles, we headed to Custom House Maritime Museum.

|

| Sailor Puppet |

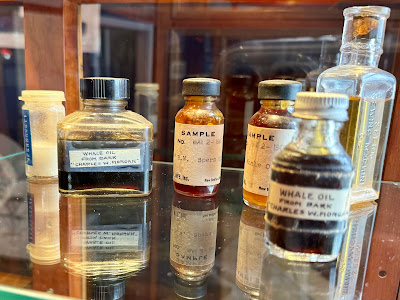

In terms of commercial whaling, New London was Avis to New Bedford's Hertz. For nearly three centuries, sailors hunted and harpooned countless whales in the Atlantic ocean. Ships functioned as small factories where strips of blubber, stripped from carcasses, were boiled to produce gallons of oil, used to light lamps and lubricate machinery. American whaling peaked in the mid-19th century before being outlawed in 1971.

Voyages could last for years. Sailors needed compact hobbies to pass the time, including wool work.

They fashioned cribbage sets from baleen, which whales use in their jaws to filter krill, the marine mammal's primary food source. Made of keratin--also found in human hair and nails--the fibrous byproduct added strength and flexibility to parasol ribs, buggy whips and corset stays.

Talented sailors also killed time carving scrimshaw from whale bone and teeth. Some 21st-century artists have substituted plastic detritus to express how man continues to damage the environment, albeit in different ways.

Knots are an essential part of maritime culture.

Randy, a former Boy Scout, tied them to earn a merit badge long ago.

The local maritime society runs the museum. The mostly unlabelled collection likely reflects their idiosyncratic contributions such as this peculiar whirligig

. . . cola sign

. . . and greeting card.

Another section is devoted to deep sea diving and the paintings of a Connecticut fishing captain or "dragger man."

This enormous, unattributed oil painting depicts the 1839 revolt aboard La Amistad, a Spanish schooner en route to a plantation in the Caribbean with an illegal cargo of men enslaved from Sierra Leone.

The men killed the captain and the cook before ordering the remaining sailors to return them to Africa. Instead, the crew headed north where the US Navy intercepted the ship off Long Island. The men were taken to New London--slavery had not yet been abolished in Connecticut--and imprisoned until their fate could be decided by the Supreme Court, the subject of an underrated but stirring Steven Spielberg movie.

Former President John Quincy Adams argued the case that earned the survivors, led by Joseph Cinqué, their freedom. American blacks raised enough money to return 35 of them home in 1842.

After visiting the museum, we dropped by the Dutch Tavern--which survived Prohibition--for a couple of beers on tap.

No comments:

Post a Comment