When Zoltan mentioned he planned to visit New York in April, I told him he could stay in my apartment for several days before I

returned from Florida.

Although he already had begun peeling the Big Apple, I suggested he catch the Gerhard Richter show in Chelsea. Audrey and I had been blown away by MoMA's major survey of the artist in 2002. Zoltan liked the "mood" works best.

That reminded me he had been obsessed with this mood indicator on my refrigerator as a child. I re-set it as soon as I got back to

47 Pianos.

|

| 1998 |

|

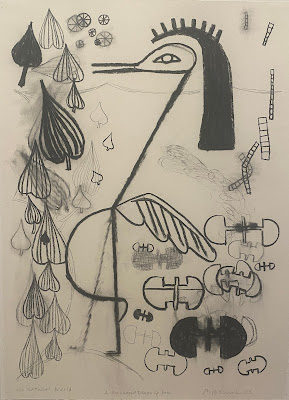

"Old Tree" by Pamela Rosenkranz

|

At the Whitney, the colors of this painting drew us both in, separately. I wasn't familiar with the artist.

If I hadn't read

a puzzling story by Rachel Cusk in

The New Yorker earlier this month, I wouldn't have known

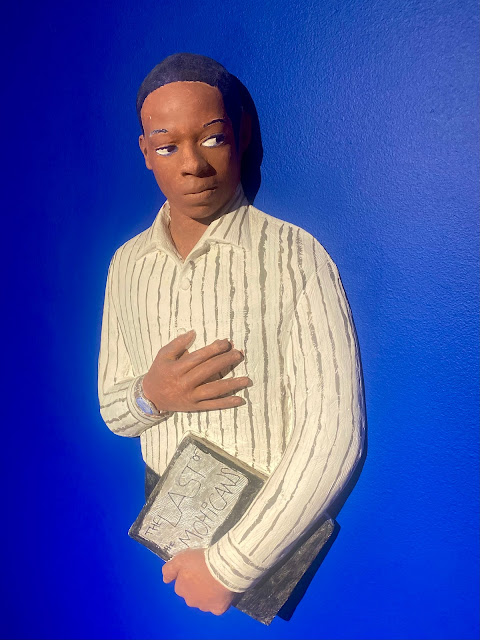

Norman Lewis, either. Mostly unheralded by the art establishment in his lifetime--he died in 1979-- Lewis was a rare Black abstract expressionist. His later work moved toward the figurative; this disturbing piece obviously alludes to the

Ku Klux Klan.

"American Totem" by Norman Lewis (1960)I knew Zoltan would enjoy the incredible views from the museum's multiple roof decks. He graciously agreed to point at another landmark building in our meta photo shoot: tall guy, even taller building.

|

In this shot, I'm pretty sure he's checking to see if his elusive friend Aaron had gotten back to him yet.

Among other things, Josh Kline: Project for a New American Century examines the plight of the American worker. After people get fired, they typically pack personal items from their desks in boxes to take home. In "Contagious Unemployment," Kline displays the contents of these boxes inside plastic containers that resemble viruses under a microscope. Very high concept.

Has automation or AI made this bagged lawyer's work obsolete? She's life-size, BTW, and not the only capitalist casualty on display.

A multi-ingredient IV drip enhances overtime efficiency!

I have no idea what Kline was aiming for in this piece but it photographed well. Eerie video interviews of actors or avatars--I couldn't tell which--impersonating Whitney Houston and Kurt Cobain make the point that entertainers are just as affected by commodification as other workers, if not even more so.

The things you find out about people when you visit a museum together--apparently, Zoltan is addicted to shredding, and not the kind St. Vincent does on her guitar. Who knew the detritus could be used to stuff a couch?

Even though Zoltan is happily employed and I'm retired, we share the same philosophy about the 9-to-5 grind, working to live rather than living to work. That probably inoculates us from some of the threats that Kline so creatively exposes. The wall behind us is covered in Patagonia-branded fabric.

After leaving the Whitney, we checked out

Little Island, just across the street. When Zoltan told me how lucky I have been to live in New York City all my life, I let him know it wasn't always this picturesque.

The waterfront was a lot more industrial when his mother and I used to ride our bikes on the elevated West Side Highway. Audrey stood on a pier close to Little Island when I took this uptown view in 1979.

Zoltan treated me to dinner at

Gennaro, my go-to Italian restaurant on the Upper West Side, where he ordered the risotto and oxtail. He was pleasantly surprised when I told him to get a spare set of keys made so he could have a place to stay whenever this snowbird flies south.

All it takes for Uncle Jeff to give you the keys to his kingdom, is a nice bottle of cabernet sauvignon and some very tasty orecchiette with broccoli & provolone. As I texted his father, "to be 33 and in Manhattan!"

Thanks again, Zoltan!