Just outside of Nuremberg, the National Socialists began building a Congress Hall in 1935 where as many as 50,000 of their party members would congregate to drink the kool aid. Never finished, it adjoins the Nazi party rally grounds.

The innkeeper at my hotel referred to it as "the colosseum," as if we were in Rome rather than the geographical center of the Nazi's extraordinary propaganda machine.

Concentration camps in the vicinity provided the hard labor for construction of a complex designed to convey strength and power. Imagine how heavy those granite blocks must have been to move and lift.

After decades of uncertainty, the site has been preserved but allowed to deteriorate as a reminder of what once was, and what could have been.

The Congress Hall, which was supposed to have a roof, forms a semicircle with a building at each end. It faces a large pond.

One building is home to the Nuremberg Symphony (rent must be cheap) which also offers outdoor concerts in the ruins during the summer. I met this mixed race family while looking for the Documentation Center, which occupies the symphony's twin. Dad, a British national who lives in Zurich, wears a Def Leppard/Motley Crue t-shirt. They were en route to Norway while Mom visited family in Shanghai.

Although the Documentation Center is currently undergoing renovation, a superb temporary exhibit provides an engrossing introduction to the rise of the Nazis.

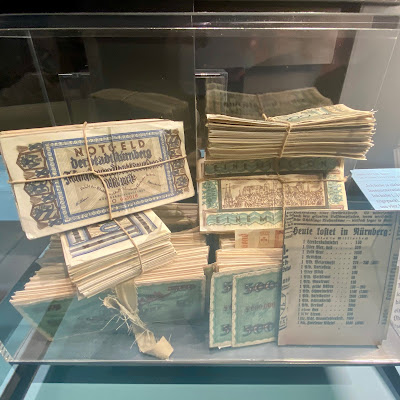

In 1923, Nuremberg printed its own "emergency" money, more readily accepted than German currency by local tradespeople and shopkeepers because of the country's sky-high inflation during the Weimar Republic.

Once the Nazis came to power, they worked to eliminate other points of view including any "degenerate" art (here exemplified by an Otto Dix work) that undercut the image of Aryan wholesomeness and German superiority.

The Zeppelin Field, designed by Albert Speer, preceded the Congress Hall in a complex of buildings planned to project the inevitability of the Nazi's domination of Europe.

In 1934, Leni Riefenstahl used the rally grounds to stage scenes of Hitler's popular support in Triumph of the Will, a film which carried images of Nuremberg and Nazi propaganda worldwide.

Here's what the grandstand of the Zeppelin Field looks like today. During the 1980s, a heavy metal music festival took place on the grounds. You can camp nearby.

Even minus the swastika which was blown off by American troops after the Allied victory in 1945, it gave me shudders to stand on the same platform where Hitler delivered speeches during his reign of terror.

Speer also envisioned a "Great Road," two kilometers long, as a parade route for Germany's armed forces. The granite pavers point to the castle in Nuremberg's old town, establishing a symbolic link with the city's past as the place where the Imperial Diet occasionally elected Holy Roman Emperors (their rule is considered the First Reich by German historians). World War II interrupted construction of Speer's "Great Road," now used as a parking lot, and he was convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials, primarily for his use of slave labor.

More Bavaria:

No comments:

Post a Comment