He began as an Impressionist in the early 1900s,

and quickly veered into Cubism . . .

before making a Dada pit stop.

His color sense can't be beat.

In 1924, Picabia collaborated with Rene Clair on "Entr'acte," a beautiful and funny surrealistic film that runs nearly half an hour. It's occasionally pervy, too.

You have to love the mourners dancing behind an edible hearse drawn by a camel through the streets of Paris.

A notorious playboy, half-Cuban and French, Picabia adored women.

He created a literal matchstick girl

and soft porn inspired some of his kitschiest work,

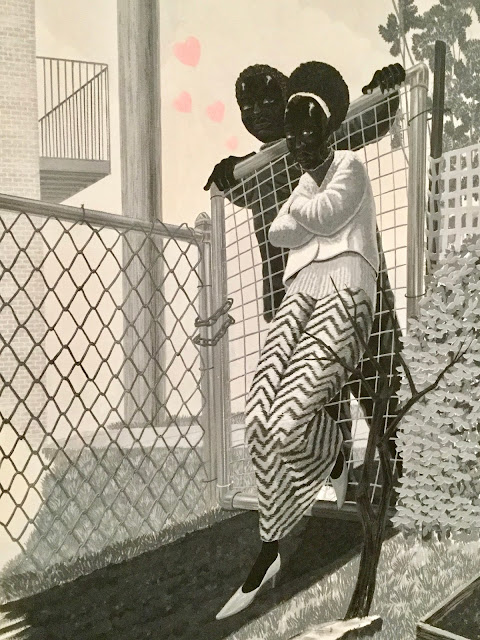

including this woman looking over his shoulder in "The Wandering Jew," an oddly titled self-portrait.

Picabia didn't take much seriously, especially coupling.

But even a committed Dadaist recognized the evils of fascism. "Calf Worship" certainly resonates today. Just add an orange wig.

Picabia crossed the finish line painting the kind of severe abstractions that leave me cold, although this upside down pig is kinda cool.

Thanks for free Friday evenings at MoMA, Uniqlo!