What would Alvin Baltrop, who died penniless in 2004 with barely any recognition, have to say about the exhibition of his photos at the Bronx Museum of Art? It's very simply hung which seems fitting given the modesty and poor printed quality of the work.

Mostly black and white, the well-composed photos document his tour in the Navy as well as his fascination with the decaying piers on the west side of Manhattan in the 70s, shortly after a Daily News headline screamed FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. It can't have been easy for a queer black man to capture the homoerotic vibe of life at sea, no matter how discreet he may have been.

The piers didn't require discretion although it's doubtful that the gay men who used them for cruising and sex welcomed Baltrop. If his photographic ID, also on display, is any indication he didn't measure up to clone standards of beauty.

I visited the area on my bike shortly before graduation from college. The World Trade Center loomed to the south, the only downtown symbol of modernity. Anyone cool sneered at the domineering twin phalluses. The carless, elevated highway eventually went the way of the piers.

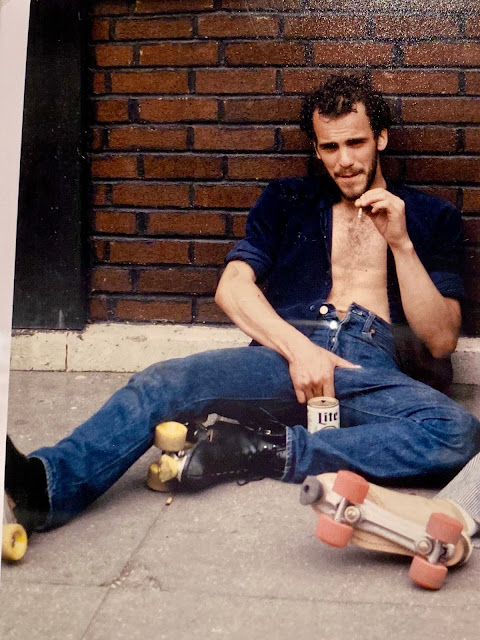

Rollerblades hadn't been invented and Baltrop, like everybody else, worshipped beer swilling, macho men.

The Chalfant exhibit recreates a subway yard in the south Bronx.

Graffiti images shot by Chalfant, whose wife Kathleen is a well-regarded actress, appear on sheets of cloth as long as actual subway cars.

Chalfant's original photos, beautifully framed and mounted, hang in a nearby room. He shot five images of a single, stopped car from a bridge with the sun behind him and later spliced them together in his studio. No "panorama" mode on cameras, then! He had to work fast because the MTA washed off the graffiti as quickly as it could.

Some taggers, as graffiti artists were known, spoofed pop art while others created their own signatures, literally and figuratively.

The Bronx museum also provides a facsimile of the Soho studio where Chalfant printed and assembled his work. His "open-door" policy for taggers helped "some weird white guy" gain their trust. Altrop, by contrast, had only a couple of cameras and needed food stamps to survive, even with veteran benefits.

Chalfant, not quite a decade older than Altrop, partied with the taggers, too. Here, Madonna gets down with Crazy Legs at Danceteria. Those were the days!

When Chalfant froze this group of taggers in time (including Crazy Legs, 2nd from the left), I wasn't much older than they were.

Chalfant also caught the movement of graffiti from the subway to the streets.

Look no further than the Grand Concourse, just outside, to find some today.

Time erases street art, too, but digital photography makes it a lot easier to preserve.

No comments:

Post a Comment