The art world has been more than a little skittish about Philip Guston during an era of acute political sensitivity. After George Floyd's murder, a traveling show organized by museums in London, Washington, DC, Boston, Houston was postponed because the artist's late-career "hood paintings," obviously alluding to the Ku Klux Klan, were included. Now the Jewish Museum has paired some of these paintings with those of Trenton Doyle Hancock, a contemporary African-American artist who identifies strongly with the older Jewish artist.

If nothing else, the discomfort with Guston's late-career works proves yet again that image overpowers reality. Born to parents forced to flee Ukraine because of antisemitic progroms, Guston incorporated white hoods into his work as readily identifiable symbols of oppression. Reacting to news of a lynching, he sketched this drawing at age 17. If I hadn't visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, I would have been surprised that lynchings took place as late as 1930.

|

| "Drawing for Conspirators" (1930) |

Shortly afterward, Guston, who had moved with his parents from Montreal to Los Angeles, and two other comrades created murals for a Marxist organization in Los Angeles that believed art could be a powerful agent of social change. Within two years, an anti-Communist squad of the police department, assisted by the local KKK chapter, destroyed the works.

|

| Mural for the Los Angeles Headquarters of the John Reed Club (ca. 1931) |

In his mid-twenties, Guston travelled to Mexico where muralists Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros influenced him and other politically-minded colleagues. After returning to America and re-locating to New York, he began creating murals for the Works Progress Administration.

|

| "The Struggle Against Terrorism" by Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish & Jules Langsner (1935) |

Spurning the conformity of the 50s, Guston eventually earned fame and critical acclaim as a member of the New York School. But by the late 60s, he broke with abstract expressionism and began painting works that recalled his early enrollment in a correspondence school for cartooning. His aesthetic switcheroo initially befuddled art critics but most eventually came around. Guston's hoods and cigars look less ominous than ridiculous, a symbol of what today might be called "toxic masculinity."

Significantly, Guston, who had changed his name from Goldstein to disguise his Jewishness (a potential impediment to success), implicated himself in the hood paintings, too, essentially saying we are all members of the Klan if we're not actively confronting racism and antisemitism in our politics.

.

|

| "The Studio" by Philip Guston (1969) |

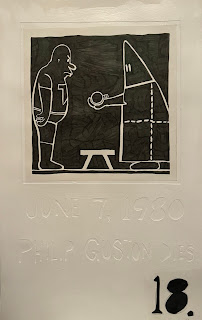

It's no wonder I became instantly enamored of Hancock, even though I'd never heard of him prior to this exhibit. He acknowledges Art Spiegelman, the artist who took on the Holocaust in Maus, in my mind the greatest graphic novel ever. Hancock took a similar tack with white supremacy in Step and Screw (2014) which features Torpedo Boy, his alter ego, and looks back to Philip Guston, whose birth and death is recorded in hard-to-see cut outs below the cartoon panels.

|

| JUNE 27, 1913 A BOY NAMED PHILIP GOLDSTEIN IS BORN IN MONTREAL CANADA TO LOUIS AND RACHEL GOLDSTEIN |

|

| JUNE 7, 1980 PHILIP GUSTON DIES |

Hancock takes the idea and runs with it, later adding a Biblical allusion to a painting that comments on the dubious social contracts that Black Americans have been forced to make as a result of white supremacy. He conveys a conversation between the Klansman and a skeptical Torpedo Boy by cutting out words from the solid color areas.

|

| "Schlep and Screw, Knowledge Rental Pawn Exchange Service" (partial, 2020) |

In this enormous work, Hancock reaches even further. He retrofits Loid, another character from his crazy vegan sci fi/superhero universe, as the lynching victim from Guston's "Drawing for Conspirators" (2nd from top above).

|

| "Coloration Coronation" (2016) |

It almost can seem as if Hancock is "sampling" Guston. Here, he nods back to Guston, his "spiritual" father, by alluding to his stepfather, who worked as a carpenter.

Guston's sense of humor is evident in Hancock's work, too, particularly in this recent homoerotic riff on the pottery scene in Ghost.

|

| "The Boys in the Hoods are Always Hard" (2023) |

Hancock renders his themes in felt, too.

Food for thought stimulated by this painting and label text which quotes Hancock: When people talk about code switching, it's often just along racial lines. But my understanding of code switching runs deeper. It becomes a superpower at the end of the day, to be able to weave in and out of a range of social situations. Is Hancock's invocation of Guston itself a form of code switching that enables him to be taken more seriously by the art world while at the same time providing cover for Guston's most controversial works? If so, it's a win-win for both artists!

|

| "Step and Screw: The Star of Code Switching" (2020) |

Update (February 2025)

Sign a petition to save this mural and others by Ben Shahn and Seymour Fogel in a federal building that is up for sale.

|

| “Reconstruction and the Wellbeing of the Family" by Philip Guston (1943) |

No comments:

Post a Comment