Two major exhibits and a bright new wing welcomed me back to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the first time since December; unfortunately, summer heat closed the Roof Garden which will not see another new commission until 2030. Unless I return before the end of October, the extraordinary sculpture of Petrit Halilaj will at least have offered a memorable final visit.

Sargent & Paris

I'm glad I saw this show after a recent episode of The Gilded Age--one of my favorite television series--aired. John Singer Sargent has been commissioned to paint the daughter of a social climbing matron who's about to be married off to an English duke in need of an American fortune--new, of course--to maintain his 16th century manor house. Their engagement is announced at the artist's unveiling of the portrait with Mrs. Astor and the rest of the Four Hundred in attendance.

|

| Self-Portrait (1886) |

|

| "Madame X (Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau)" (1883-84) |

|

| "Smoke of Ambergris" (partial, 1880) |

|

| "Dr. Pozzi at Home" (1881) |

|

| "La Vicomtesse de Poilloue de Saint-Périer (Marie Jeanne de Kergolay)" (1883) |

The French government purchased this vibrant portrait of a flamenco dancer for its museum of contemporary art. Sargent already had made a name for himself by the age of 36.

|

| "La Carmencita (Carmen Dauset Moreno)" (ca 1890) |

|

| Albert de Belleroche (1883) |

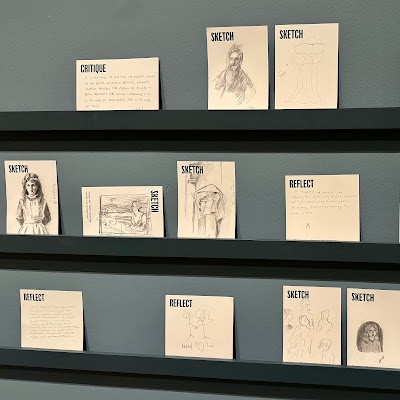

The Met encourages visitors to express their own creativity at the end of the exhibit. The quality of the pencil sketching was surprisingly good says the man who barely can draw stick figures.

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style

I'm embarrassed to admit when I first learned that the Costume Institute was devoting a show to Black "dandies," a term I mostly associated with Edwardian England, I pictured over-the-top pimp finery. Instead, the museum celebrates Black men dressing well as a triumph over adversity and stereotype.

Nearly two and a half centuries separate these depictions of how other people see dandies and how they see themselves. In this racist caricature, a British artist lampoons the stylish "pretensions" on display

|

| "The D- of [ l-playing at foils with her favorite lap dog Mungo after expending near £10000 to make him a -*" by William Austin (1773) |

This beloved New Orleans gentleman, celebrating his 76th birthday, played bass drums and kazoo in the Treme Brass Band. By pinning dollar bills to his jacket, Lionel Batiste amplified his good fortune and literally made himself look "money."

|

| "Uncle Lionel's Birthday" by Andy Levin (2007) |

|

| Jacket by Emeric Tchatchoua (Autumn/Winter 2019-20, 3.PARADIS) |

Mannequins wearing clothes mostly designed during the new millennium appear throughout the exhibit in various contexts.

Although well chosen and beautifully displayed, the outfits sometimes seemed a little superficial in comparison to the more historical items also on view.

|

| Ensembles by Kerby Jean-Raymond (Spring/Summer 2020, Pyer Moss) & Edvin Thompson (Spring/Summer 2025, Theophilo) |

|

| Ensembles by Skepta (Spring/Summer 2025, MAINS) & Polo (2019, "Morehouse College") |

|

| "Miss Stormé de Larverie, The Lady Who Appears to be a Gentleman, New York City" (1961) |

Here's what Frederick Douglass had to say about this elegant timepiece from 1846: "The possession of a watch in my young days was among the remote possibilities. I did not own myself."

Minstrel shows with white men performing in blackface during the 19th century initially acclimated Americans to seeing "Blacks" in formal dress, but 20th century entertainment--including vaudeville, Broadway and Hollywood--finally provided them with a wider platform to express their well-attired talent, sometimes subversively. "Cakewalk" dances like these recorded in 1903 were once a coded way for slaves to make fun of their highfalutin' owners.

Harlem's emergence as the cultural capital of Black America provided its residents a relatively safe space to develop their own highly developed, idiosyncratic style, including the zoot suit, a fashion trend soon imitated worldwide.

|

| "Harlem Dandy (African American man [head & shoulders] wearing a hat with tilted brim) by Miguel Covarrubias (ca 1930) |

|

| "Zoot Suit" by Charles Henry Alston (ca 1940) |

This dance routine featuring the Four Step Brothers and Harold Nicholas from Carolina Blues (1944) puts a Hollywood spin on Harlem dandyism.

The suit worn by Nicholas nods to Lucius Beebe, truly a Harlem Renaissance man, who sported something similar when he posed for the cover of Life magazine five years earlier. His new look had sounded the death knell for the zoot suit in the Black community.

Needless to say, my family didn't subscribe to Ebony or Jet when I was a teenager.

But Time, Life and Look all included images of the Black Panthers who raised my consciousness about fashion as much as racial inequality. Revolution never looked so good.

Just a few years later, athletes like Walt Frazier became Black male fashion plates. When he endorsed an athletic shoe--the first professional basketball player to do so--Puma named it "Clyde" (seen below along with one of his wide brim hats) because of Frazier's fondness for the gangster look he appropriated from Bonnie & Clyde.

In "Looking for Langston" (1989), an absolutely fascinating meditation on Black queerness, Isaac Julien imagines a venue full of tuxedo clad men and women, including Langston Hughes, disguising their sexuality in conformity, another form of passing.

.

A stack of monogrammed Louis Vuitton luggage owned by André Leon Talley near the end of the exhibit also subtly acknowledges queerness, this time flamboyant, in the fashion world. It's hard not to wonder what ALT would have made of "Superfine" which, as far as I can recall, didn't include any caftans.

Arts of Africa, Ancient America & Oceania

|

| West Papuan Spirit Canoe (partial, 20th Century) |

|

| West Papuan Paddles (Early to mid-20th Century) |

Sunlight illuminates these imposing slit gongs from Vanautu, no more than a century old.

No worries about the provenance of this ceremonial house ceiling from Papua New Guinea: The Met commissioned it in 1970 from artists in Mariwai, a village home to two different clans.

Nearly 200 painted palm leaf stems allude to the villagers' dual clan heritage and their environment, including flying foxes, natural spirits, and the play of light on water in Oceania, which encompasses thousands of Pacific islands, Australia and New Zealand among them.

Contemporary art from Oceania also is exhibited, including colorful variations of bark paintings similar to those that I saw at a gallery show last year.

|

| Baratjala Series by Nonggirrnga Marawili (partial, Australia, 2022-23) |

Exhausted, I didn't spend as much time in the African or Central American galleries.

|

| Initiation Headdress (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Late 19th-first quarter of 20th Century) |

|

| Throne of Njouteu (partial, Cameroon, Late 19th-Early 20th Century) |

|

| "Tabaski III" by Iba Ndiaye (1970) |

The objects from Central and South America are significantly older than those found in the African and Oceanian collections, perhaps because stone is a much more durable medium. Nevertheless, displaying them in such close, thematic proximity seems forced. They deserve more distinct treatment, like they get at the incomparable Volcanica in Mexico City.

|

| Seated Elder (Columbia or Ecuador, 200BC-300AD) |

|

| Feathered Tunic (Peru, 1450-1625) |

No comments:

Post a Comment