Kelly Lytle Hernández won the

Bancroft Prize for her account of the (mostly) men who fomented the Mexican Revolution while

my tour of the nation's capital city was coming to an end. Although I rarely read history books, I thought it would help me overcome my dawning (and inexcusable) ignorance about a childhood neighbor. Mission accomplished, but like

The 1619 Project,

Bad Mexicans left me utterly dismayed with the pervasiveness of white supremacy in American history.

Not that Ricardo Flores Magon, the soul of the Mexican Revolution, would have been surprised, A closeted anarchist who eventually declared "solemn war on Authority, Capital and Clergy" he and his compatriots, the majority of whom were socialists, formed the Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM ) party and published Regeneración, a radical newspaper that raised the consciousness of Mexicans on both sides of the border. The reader quickly realizes that today's immigration problems haven't changed much in more than a century and that Mexican history can't be understood without American history and vice versa.

And what a sad, exploitive history it has been, aided and abetted by both the Mexican and American governments. The magonistas as they were known rebelled against dictator Porfirio Diaz, who sold his country's natural resources and labor to the Yankees like the Guggenheims, the Hearsts and the Rockefellers. His corrupt government justified killing as many as 10,000 people, justifying these murders with ley fuego or "law of flight" which gave his lackeys authority to shoot rebels in the back.

The U.S., for its part, passed "Juan Crow" laws that stripped Mexican Americans of their rights and property. Hernández describes these laws in the context of how the US government used them to try to deport magonistas living in the U.S. (Magon himself holed up in St. Louis, of all places, for a time) and acknowledges the power (and occasional) fairness of our state court system (even in Texas!) which ruled that Mexicans have a right to become naturalized citizens. She also exposes the US Post Office's efforts to keep the Diaz government informed of the magonistas' whereabouts and activities. Ironically, though, the complicity of the postal authorities led to the treasure trove of letters that enabled Hernández to document the magonista movement so thoroughly. She found most of their illegally obtained correspondence archived by the Mexican government.

Ultimately, the Porfirato collapsed after the aging dictator for whom it was named made a strategic error by making it more difficult for Americans to profit from their South of the Border exploitation. The U.S. refused to intervene as the revolutionary seeds sown by the magonistas began to ripen, and anti-Americanism in Mexico reached a fever pitch. A civil war ensued after Franciso Madero, the rich, Berkeley-educated, liberal “spiritist” who sought counsel from his dead brother was assassinated just two years after succeeding Porfirio in a democratic election. The magonistas, much diminished in number as soon as Magon came clean about his anarchism, flamed out after ill-advisedly but understandably embracing a little-known 1915 invasion of Texas by Mexican nationals who aimed to unite people of color against Yankee tyranny. They were slaughtered and Magon was convicted of sedition. He died in prison, although when he was repatriated to Mexico, he was given a state funeral.

Hernández has given Magon his belated due but you can be damn sure that American children will never be taught this history. If they were, how they could they ever pledge allegiance again?

|

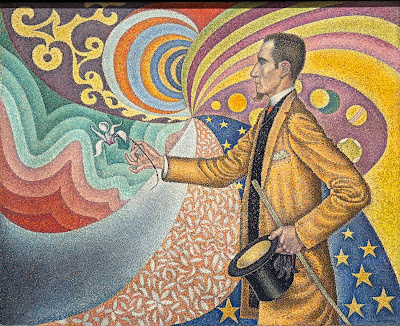

| Ricardo Flores Magon by Diego Rivera (1947) |