If I'd been better versed in the conflict's history, I might have realized why Poland's Museum of the Second World War--a "must-see" attraction according to every guide book--was located in Gdańsk: it's where the Nazis launched their invasion of Poland in September 1939. Unexpectedly, given the towering presence of the building, the permanent exhibit is completely underground. It represents the past, according to the local architectural firm that designed it.

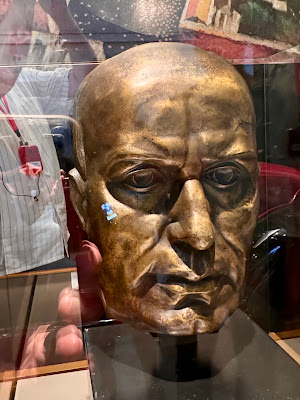

The museum does a thorough job of examining the conditions that led to the rise of the National Socialists in Germany and the anti-Semitism they propagated. I'd never seen a bust of their leader.

This poster advertises a "documentary," produced under the auspices of Joseph Goebbels, that includes scenes shot by the German military in the Warsaw and Lodz ghettos. It compares Jews to rats, as sources of contagion.

Poles who physically appeared to be Aryan could become citizens of the Third Reich provided they demonstrated their allegiance, such as through service in the armed forces.

The Nazis even recruited SS members in Norway.

A week before Hitler invaded Poland, he signed a non-aggression pact with Stalin, which included a plan to divvy up the Eastern European countries that lay between Germany and Russia.

Although the plan remained secret until the Nuremberg trials, Stalin invaded Poland soon after the pact was signed under the pretext of--get this--protecting the sovereignty of Ukraine and Belarus. The Emperors of Austria, Prussia and Russia had partitioned the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in much the same way 150 years earlier. If history doesn't always repeat, it certainly echoes.

The deeply Catholic Poles had good reason to fear a Soviet takeover. An exhibit illustrates how the Soviets transformed "red corners" in Russian homes--traditionally an area where residents displayed their religious icons--into shrines honoring the Bolsheviks that became known as "little red corners" where politics supplanted prayer.

Nazi Germany used propaganda to exploit fears of communism across Eastern Europe, like this poster from Czechoslovakia depicting Prague's iconic castle with a tag line that sounds right out of a horror movie: "When they grab you, you will die."

While the museum primarily focuses on the Polish experience of the war, it also includes exhibits about the rise of fascism in Italy and Spain.

|

| Il Duce |

|

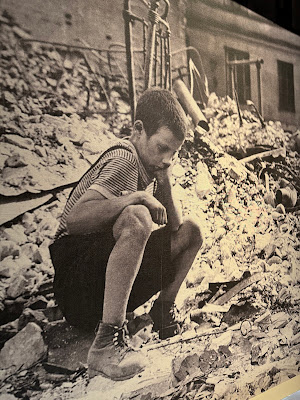

| Spanish Civil War |

Another gallery looks at countries whose governments took the easy way out, like Vichy France.

There's even a section devoted to Japan. General Hideki Tojo ordered the attack on Pearl Harbor, ending the neutrality of the United States on December 7, 1941, "a date which will live in infamy" according to President Franklin D. Roosevelt who, until then, had managed to ignore events in Europe.

The Japanese, like the Germans, inculcated warmongering at an early age.

One enormous gallery recreates a Warsaw street during the Nazi occupation.

Here's what that same street looked like after the war.

Through a combination of exhibits like these, artifacts and extensive historic video footage, the museum does a superb job of recreating the almost unthinkable hardships of the war years. It left me feeling extraordinarily fortunate never to have experienced anything remotely like them.

By 1944, as many half a million Poles had joined the resistance which supported pre-war government officials exiled in London.

The resistance brought its full force to bear during Operation Tempest, launched in 1944 as the Red Army advanced on Nazi forces occupying Poland. The exiled government hoped to liberate the country from the Nazis and re-establish its pre-war borders, prior to the arrival of the Soviets. The strategy failed; Nazi bombing mostly obliterated Warsaw after the Uprising and Stalin was able to grab Poland (and other Eastern Bloc countries) after the Yalta conference, which included a declaration that communists should be included in Poland's new government. As a result, it remained under Soviet rule for four more decades, until the USSR collapsed.

The museum also examines how some Poles risked their lives to save Jews from the Nazis including this baby girl, one of 2,500 children rescued through the efforts of Irena Sendler. The child's mother included a silver spoon engraved with her daughter's name and date of birth in the basket, concealed in a cartload of bricks, that took her from the Warsaw ghetto to the "Aryan side." Elzbieta Ficowska--whose parents and grandparents died during the war--kept her lucky spoon all her life.

After spending more than three riveting hours in the museum, I discovered that it has been buffeted by political winds since its conception in 2008 as a local museum to commemorate Westerplatte, the nearby peninsula where the Poland tried to defend itself against the Nazi invasion.

Under the leadership of Donald Tusk, a liberal prime minister (and native of Gdańsk) who eventually assumed the presidency of the European Council, the mission of the museum expanded to become a definitive depiction of World War II from the Polish point of view. But by the time the galleries finally opened in 2017, Poland had elected a right-wing government that seems to have spent as much time interfering with the curation of the museum as it did destroying the judiciary's independence.

Elimination of any ambiguity about the fact that many Poles had collaborated with the Nazis was first and foremost on the agenda of the Law and Justice Party. This led to an overemphasis on Polish resistance fighters and citizens who had harbored Jews, forcing the resignation of some academic curators and the re-training of guides. Visitors keen to experience a more nuanced look at Polish behavior during the war found a jingoistic film in the final gallery particularly objectionable.

I don't recall seeing such a film, although I was pretty exhausted by the end of my visit, less than a year after Donald Tusk's re-election as Polish prime minister. I can say that it left with me with the conviction that people who lived in Poland from 1939 to 1990 were dealt an awful blow by history.

More Poland

Gdansk:

Kraków:

No comments:

Post a Comment