When in Rome, do as Romans; when in Poland, order pirogen, as Christine did several times, including at Zapieeck, a themed restaurant on a busy Warsaw thoroughfare. A flag planted with a toothpick announced the ingredients inside the pillowy dough. "Champignons, with hard cheese."

What appeared to be a handicapped pierogen greeted patrons on their way to the restrooms downstairs.

Waitresses even wore pierogen-patterned skirts.

Tourist trap aside, I really had to up my food game traveling with Christine. Fruit lunches after hearty buffet breakfasts weren't going to cut it, as I learned in Gdańsk, where her pierogen were served with real style. Yep, she's part Polish.

I stuck with a delicious vegetarian option. A waiter kindly instructed us always to pay in zlotys. "Your credit card's exchange rate always will be more favorable than the restaurant's," something I already knew but I increased the size of his tip anyway. Apparently servers in Poland--where the average income is just $2,000 per month (compared to $5,500 in the US)--are paid living wages and don't expect 20% tips from their countrymen. Tourists, however, are a different story.

My first meal in Poland was also the most colorful. Cold borscht (and beer) really hit the spot after climbing to the top of St. Mary's bell tower.

For dinner, I compiled a list of starred restaurants in the Lonely Planet guidebook, including Restauracja Gdańska, noted for its over-the-top decor and traditional Polish cuisine. It took two lengthy phone calls from our hotel concierge to reserve a table. Even though the place was empty when we arrived, the maître d' greeted us with suspicion. Would a secret word unlock one of the outdoor tables marked reserved? He seated us beneath autographed photos of notable Poles, including Pope John Paul II and Lech Wałęsa.

My "Presidential Herring," served with bread and a thick slab of butter, was superb.

But it turned out pork shank isn't my thing and I traded my sauerkraut for Christine's red cabbage. The well-seasoned, roasted potatoes really hit the spot.

Somebody left behind an empty bottle of vodka near the entrance of the European Solidarity Center.

My scallops at a Thai restaurant in Sopot, served in clam shells on a bed of rock salt, were way more photogenic than filling. Christine shamed me out loud in front of the waitress when I reduced the size of her tip after she informed us that a ten percent service charge had been included in the bill. "Maybe I wouldn't have if she had remembered to bring me the beer I ordered."

The food at Glonojad, a vegetarian restaurant just beyond Florian's Gate in Kraków was so tasty, filling and inexpensive that we went back for a second meal.

Buzzing hornets interfered with the consumption of my birthday cake at an outdoor cafe in Rynek Główny, ordered in lieu of lunch. Later, I somehow forgot to photograph the very strange celebratory dinner we had at Foggy Yami where the sushi rolls were as big as logs. I packed my leftovers for lunch the next day which resulted in a concept that would make a great name for a punk band: Sushi at Auschwitz. It definitely felt very weird.

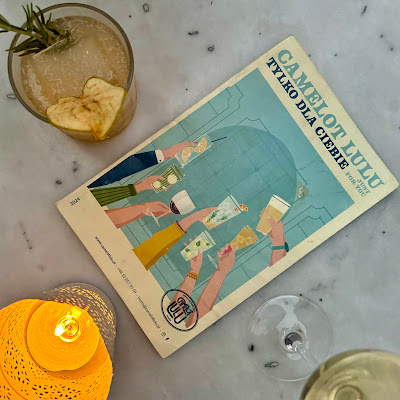

Camelot Lulu's cocktails in Kraków lured us back to an excellent meal as well the following evening.

A late lunch at Joel Sharing Concept, an Israeli restaurant we stumbled upon in Warsaw near Łazienki Park, started with wine for Christine and ice-cold beer for me in a bewitching bottle.

Our appetizers and entrees were the best of the trip, so good that I recommended them to the Norwegian tourists who sat down after us.

We finally got the chance to dine at a so-called "milk bar" (no alcohol served) our final day in Poland. A remnant of the Soviet era, it offered filling food at unbelievably cheap cost, if you didn't mind the sullen young women behind the counter who spoke no English and made us photograph our orders from the overhead display menu. I finally had pierogen, so filling I didn't need to eat again that evening.

More Poland

Gdansk:

Kraków:

No comments:

Post a Comment