My youthful ignorance and fatalism (how could striking workers expect a communist government to meet their demands?) prevented me from appreciating just how much labor organizer Lech Wałęsa managed to accomplish, but a visit to the extraordinary European Solidarity Center rectified that. What didn't interest me much in my thirties suddenly became fascinating through a combination of my own maturity and state-of-the-art exhibition of historic material.

The Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970 towers above the Center. It opened a decade ago, on the 44th anniversary of the Gdańsk Agreement which led to the creation of Solidarity, the independent trade union that accelerated the end of communist rule in Poland.

The monument was installed near what was then the entrance to the Lenin Shipyard, shortly after Poland's government and Wałęsa signed the agreement that made news around the world. Anchors hang from its three crosses, each more than 100 feet tall, and flowers form another at the base. Tens of thousands of Poles attended the dedication ceremony on December 16, 1980.

Bas reliefs depict shipyard workers in Gdańsk and several other Polish coastal cities who struck to protest a government increase in food prices while wages stagnated, the same issue that sparked the 1980 strikes a decade later. Wałęsa was 27 when he participated in the first.

As we soon learned, government authorities murdered more than 40 workers during the initial strikes. All were subject to surveillance.

This bullet-ridden jacket belonged to ship builder Ludwik Piernicki, just 20 when he was killed on December 17, 1970, the bloodiest day of the strike. His pocket contained a medallion of the Virgin Mary and a blood donor card that noted Giving blood is the greatest of humanitarian acts, proof of great social solidarity. Although the label didn't indicate if this irony explains the union's eventual name, it certainly makes a great origin story.

Neither Christine nor I could believe the size of Center, just inside the Gdańsk Shipyard, designed to evoke the enormous tankers manufactured nearby.

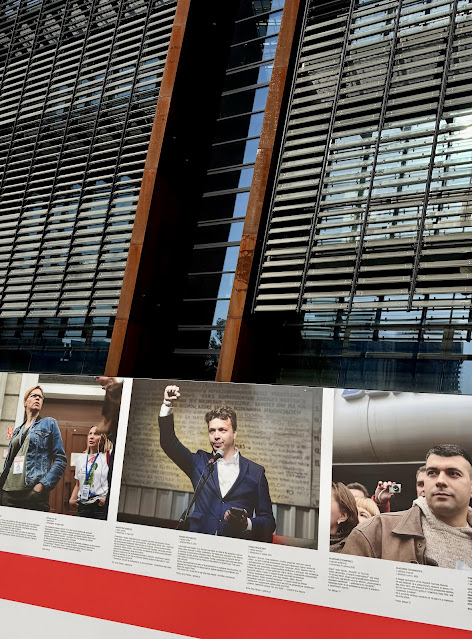

An outdoor exhibit highlights Roman Protasevich and other Belarusian dissidents protesting that country's oppressive, pro-Russian government.

Once inside, we realized the Center also hosts conventions. Dozens of camera manufacturers had set up booths on a Saturday morning, which explained a woman at the entrance who had been dressed in a gown fabricated from what appeared to be Polaroid pictures.

If you look mid-right at this photo, you'll see that the elevators are branded with yellow peace or victory signs, I couldn't tell.

We spent more than three hours perusing the permanent exhibit. The first gallery recreates the shipyard including a locker room

. . . complete with photos and interviews with actual workers

Hard hats decorate the ceiling above a factory floor.

More than a thousand ships have been built at the Gdańsk Shipyard since its founding in 1946. At its peak, more than 20,000 people worked there. One-tenth that number are employed today.

This map, which shows areas of striking workers, makes it clear why the Polish government capitulated to Wałęsa's demands a few days earlier. Strikes had broken out all over the country.

Needless to say, the Kremlin wasn't too happy about the situation in Poland despite the "brotherly friendship" between Leonid Brezhnev and Edward Gierek, the Polish head of government who permitted Solidarity to form. Gierek was soon ousted.

Soon after the Soviets installed General Wojciech Jaruzelski, a more doctrinaire and pitiless stooge who, as the puppet head of the Polish government, imposed martial law. And gave sunglasses a bad name. He also banned Solidarity on the grounds that doing so would forestall a Soviet invasion.

In a video interview, British-Polish photographer Chris Niedenthal explains how he feared for his own safety when he took this iconic shot in Warsaw from a second-floor window shortly after Jaruzelski began to crack down on Poland's liberalization. With Russian-manufactured Polish tanks.

Jaruzelski had Wałęsa and other leaders of Solidarity arrested.

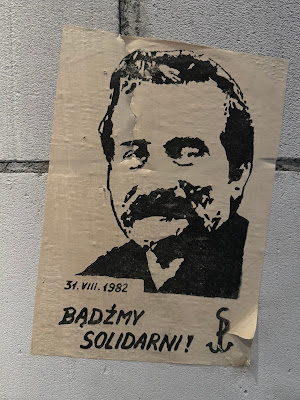

The movement went underground. Released after eleven months of incarceration, Wałęsa returned to his old job at the Gdańsk Shipyard as an electrician, albeit one who soon would win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Solidarity members, by now ten million strong, began wearing tiny electrical resistors to demonstrate their support for Wałęsa and the trade union that changed the course of Polish history.

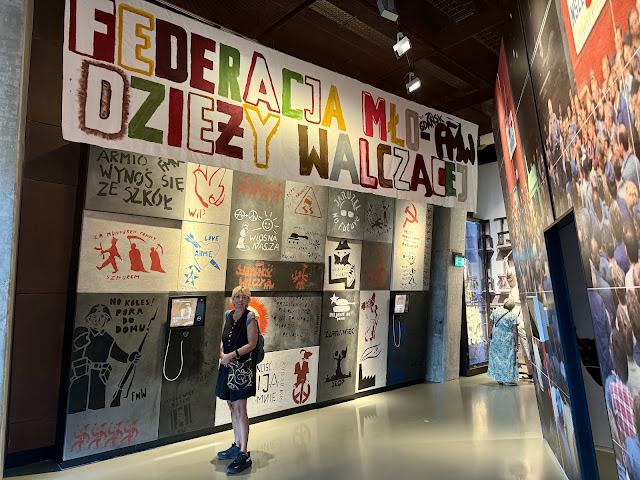

Neither Jaruzelski nor the Soviets could control public opinion during the demonstrations and deteriorating economic conditions that followed for much of the 1980s, particularly with Pope John Paul II and the West offering support for Solidarity. Local graffiti artists were witheringly prolific.

The Polish government countered with its own crude propaganda campaign that emphasized Poland's historical grievances with its neighbor to the west. This poster depicts President Ronald Reagan and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, after the U.S. and Western Europe applied sanctions against the Jaruzelski government, declaring that the crusade against Poland began in the Middle Ages with the Teutonic Knights.

But by the end of the decade, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had embraced perestroika, the Polish government initiated weeks of talks with Wałęsa and more than 400 other participants representing both Solidarity and the government. Here's the room where democracy began to bloom in Poland after the Round Table Agreement was signed in April 1989.

I'm seated in Wałęsa's chair.

The Round Table agreement legalized trade unions, introduced the office of the presidency, eventually unseating the Soviet overlord (Jaruzelski, the only candidate on the first ballot, assumed office for a year before Wałęsa himself was elected in late 1990), and created both a National Assembly and a Senate. Solidarity became a political party. Anyone who doubts the pervasiveness of American pop culture need only see how the new party branded itself with Gary Cooper's High Noon image, a courageous sheriff who unflinchingly stood his ground against the bad guys. If Reagan had been in better movies, that could have been his image on the wall.

In the first elections after the Round Table Agreement, Solidarity candidates won 35% seats in the National Assembly (as many as were available) and 99% of the Senate seats. It appears as if Wałęsa campaigned with each and every one of them!

A final gallery enables visitors to weave their comments on Solidarity's inspiring story into a tapestry that showcases the brilliance of its logo.

|

| The Cardiogram (1980) |

More Poland

Gdansk:

Kraków:

No comments:

Post a Comment