A rainy forecast dictated the inside itinerary of our first day in Kraków, a little more than five hours south by train from Gdańsk. First stop: Oskar Schindler's Enamel Factory, where we had to wait in line for an hour because it's free on Monday mornings. The inscription on the commemorative plaque quotes from the Talmud: "Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire."

Aside from the plaque, nothing about the nondescript building suggests you are about to experience another very serious lesson in Polish history.

After the Nazis invaded Poland, they set up the headquarters of their occupation in Kraków, one of Poland's oldest and prettiest cities. As a result, it mostly avoided the destruction experienced by many other European cities during World War II.

The museum vividly documents the Nazi occupation. It's hard to overestimate the significance of this rubber stamp on ordinary life from 1939 until 1945, when the Red Army invaded and began arresting Poles loyal to their government in exile.

Upon arrival, the Nazis attempted to destroy Polish culture by tearing down historic statues

. . . and minting new street signs in German. ("Hbf." means Hauptbahnhof or railroad station).

Jews comprised nearly a quarter of Kraków's 250,000 residents. Almost immediately they were forbidden to use public transportation.

Nazis humiliated Orthodox Jewish men by removing their facial hair in public.

Some Jewish women were required to sweep snow from the streets. From the expression on their faces, it's pretty clear they don't recognize that the unimaginable is hurtling towards them like an express train.

They soon were required to wear identifying armbands.

By 1941, the Nazis forced Jews to live in the Podgórze district, where Schindler's Enamel Factory was located. The gated ghetto resembles the entrance to a Hollywood movie studio.

But Jews had to carry their papers--with the Nazi rubber stamp--to get in and out at all times.

The Nazis established Jewish citizen councils, called the Judenrat, ostensibly to improve communication with the group whose lives they were about to obliterate. The Kraków Judenrat produced this demographic analysis of the ghetto.

Photos, artifacts and dioramas in the museum depict daily life in both the ghetto and non-Jewish areas of the city.

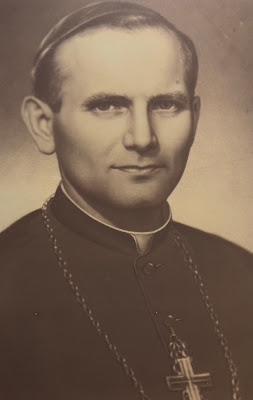

Shortly before the Nazi occupation, Karol Wojtyła began his studies at Jagiellonian University, Poland's most respected institution of higher learning (employing academics purged by both the Nazis and the Soviets). He also performed in the underground theater. Like all able-bodied males he was required to work and became a manual laborer. He also began attending the seminary in secret.

Film director Roman Polanski, a resident of the ghetto, would have been about the same age as this little girl. He survived by living in foster homes with false identity papers.

But you know how the story ended for most Jews in Poland. By March 1943--shortly before the tenth anniversary of the beer hall putsch in Munich, the event that brought Hitler to prominence--the Nazis had liquidated the ghetto and sent tens of thousands of local Jews to their death.

One exhibit shows some of the possessions they were forced to leave behind and which the Nazis plundered.

There's surprisingly little about Oskar Schindler in the museum, aside from a documentary film featuring one Jewish and two Christian employees of the factory speaking about their boss. This photo sits on his office desk.

Despite the immortality he achieved as a result of Steven Spielberg's film, the museum does an excellent job of humanizing him--his primary professional talent was black marketeering, which came in handy when feeding his workers--and keeping his heroic contribution in thoughtful, non-sentimental perspective: Schindler saved 1,200 Polish Jews; three million more perished as a result of forced labor or being gassed in concentration camps.

Here's Amon Göth, commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp, where many of the city's healthy Jews were sent after the liquidation of the ghetto to work as slaves for the Third Reich.

Not all Nazis napped shirtless with their dogs. Some held them up by the scruffs of their necks.

It begs the question: how can such normal-looking people be so evil?

More Poland

Gdansk:

Kraków:

No comments:

Post a Comment