It's a wonder that it took me so long to discover this

Pulitzer-prize winning novel--a satire of American imperialism narrated by a double agent and written by Vietnamese man who fled his divided country in 1975 after the U.S. withdrew its forces, eventually becoming a professor at the University of California--that now also has been adapted as an HBO series.

Viet Thanh Nguyen's native land has been a source of fascination ever since

my father returned from Saigon a changed man, disillusioned by a military government that reported actual "fake news" long before it became a political platform. And I've also seen for myself the yin and yang mindsets between the country's

north and

south--Nguyen lived in both as a child--that continue to battle for dominance half a century later despite the unification of the

Socialist Republic of Viet Nam.

The Sympathizer grabbed me immediately in a way that novels by

John le Carré and

Graham Greene haven't, perhaps because the stiff-upper-lip Englishness of their characters kept them at some cool remove. Not so the bravura and endlessly quotable voice of

The Sympathizer's anonymous spy which at times sounds a bit like

Alexander Portnoy's. Nguyen even ups the ante, in what only can be a deliberate nod to

Philip Roth: his narrator uses a squid instead of a liver to achieve adolescent sexual satisfaction before declaring, as an adult:

I, for one, am a person who believes that the world would be a better place if the word “murder” made us mumble as much as the word “masturbation.”

Like his conflicted spy, who is sent by his North Vietnamese handlers to college in California during the 60s, Nguyen knows America in a way that its natives do not. He also writes as well or better than most of my favorite contemporary American authors, and his frequent allusions to '60s pop culture always hit their mark.

Although every country thought itself superior in its own way, was there ever a country that coined so many “super” terms from the federal bank of its narcissism, was not only superconfident but also truly superpowerful, that would not be satisfied until it locked every nation of the world into a full nelson and made it cry Uncle Sam?

Nguyen is just as fluent in identifying prejudices against "Orientals," among whom Americans refuse to distinguish.

We were strange aliens rumored to have a predilection for Fido Americanus, the domestic canine on whom was lavished more per capita than the annual income of a starving Bangladeshi family. (The true horror of this situation was actually beyond the ken of the average American. While some of us indeed had been known to sup on the brethren of Rin Tin Tin and Lassie, we did not do so in the Neanderthalesque way imagined by the average American, with a club, a roast, and some salt, but with a gourmand’s depth of ingenuity and creativity, our chefs able to cook canids seven different virility-enhancing ways, from extracting the marrow to grilling and boiling, as well as sausage making, stewing, and a few varieties of frying and steaming—yum!)

But beneath the double agent's hyper-articulate cynicism beats a lost boy's heart. Fathered by a French Catholic priest who teaches but never claims his progeny, the narrator loses his fiercely loving mother, a North Vietnamese peasant, while attending college in the States. Much later, his handlers on both sides support his assignment to help

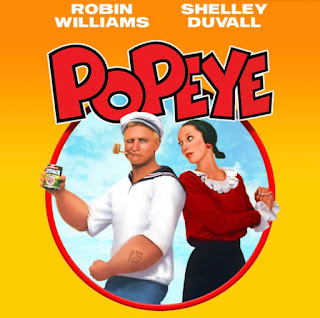

Francis Ford Coppola, oops, I mean "the auteur," cast some actual Vietnamese in

his upcoming movie blockbuster, giving it a patina of Hollywood verisimilitude. On set, the narrator encounters a graveyard complete with fake tombstones and personalizes one for his mother, a gesture I found so touching, perhaps because

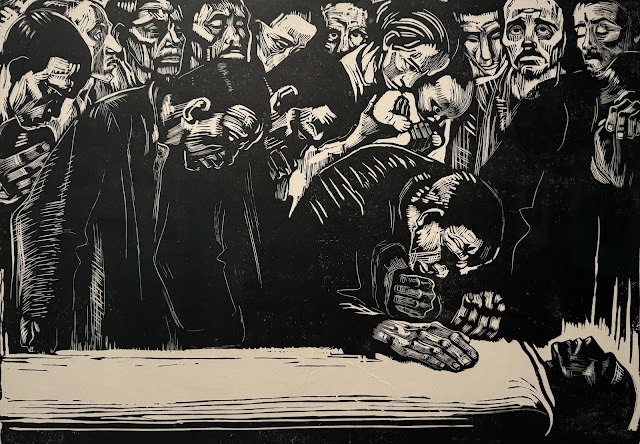

I lost mine at the same age, that I almost could forgive him for two murders his sentimental allegiance--strengthened by two actual blood brothers--forces him to commit.

On the gray face of the tombstone I painted her name and her dates in red, the mathematics of her life absurdly short for anyone but a grade-schooler to whom thirty-four years seemed an eternity. Tombstone and tomb were cast from adobe rather than carved from marble, but I took comfort in knowing no one would be able to tell on film. At least in this cinematic life she would have a resting place fit for a mandarin’s wife, an ersatz but perhaps fitting grave for a woman who was never more than an extra to anyone but me.

The Sympathizer hits a speed bump near the end when it turns more philosophical, perhaps even nihilistic, ending with uncertainty rather than resolution, and invoking another great American novel: Thomas Wolfe's

You Can't Go Home Again. Nevertheless, waiting a decade to read Nguyen's terrifically entertaining novel had its advantages: I can read his sequel,

The Committed, sooner rather than later, while hoping that he finally shows his hand.