|

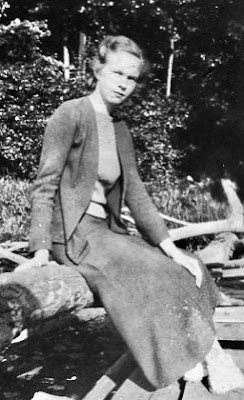

| Falls Church, VA (April 1957) |

The weather in Milagro (“miracle”) Hills, if not the culture, definitely agreed with Mary. Decorating the first home of her own with Danish blonde furniture and playing bridge with neighbors kept her busy enough once I began school. She finally stopped smoking when a doctor warned she’d have to carry around an iron lung on her back if she didn’t.

|

| Milagro Hills (1959) |

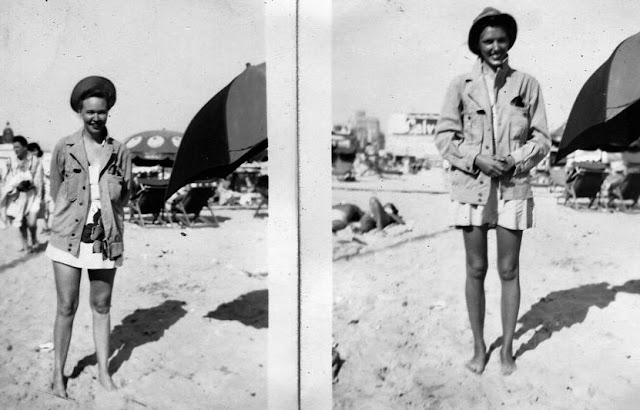

|

| Parrot Paradise Ormond Beach, FL (1960) |

|

| Army wife with Col. Walton & Maj. Houston Payne (1962) |

|

| White Plains, NY, with Jeff & mother-in-law Edith Hon (1962) |

The Cold War threw a curve ball at her placid suburban existence shortly after the Cuban missile crisis. When the Army transferred Ken to France we had to stay put until geopolitics settled enough for us to join him, although Mary was thrilled about the prospect of living in France. Still, in what may have been an act of passive aggressiveness, she didn’t waste any time getting me a puppy—Ken never would allow it—just as she had bought me a portable television set to watch “The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends” and “I Love Lucy” before he left. No fan of TV either, he couldn’t understand the need for two sets.

We shipped Taffy, our snappish cocker spaniel, to

Orleans ahead of us, spending several uncertain weeks in White Plains with Sis and her husband, Robbie, until the Army confirmed our travel plans. They picked us up at Idlewild Airport in their white 1957 Thunderbird with a red interior. But something went awry between Mary and Sis; they stopped speaking for years after our visit. I found the loss of my favorite aunt bewildering.

To look at our passport picture, you never would know Mary was as sick as she was. Ken had rented a house within walking distance of the Loire with a bakery so close that I could pick up fresh croissants for breakfast. We took frequent day trips to local chateaux and Paris, which Mary loved more than any other city and where she picked up reproductions of her favorite artists, Maurice Utrillo and Bernard Buffet. But soon she had to be hospitalized and have her spleen removed. Ken requested another transfer, this time to Heidelberg, closer to the only Army medical center that might be capable of diagnosing her illness. The move meant we had to leave Taffy behind.

|

| 1962 |

Looking back at that period, the bleakest of my childhood, I realize that Mary may also have been facing mental health issues or at least a serious marital strain related to Ken’s frequent work-related travel. She and Ken argued so angrily one night at dinner that I, a nine-year old boy, rose from the wooden bench in our small kitchen to defend her. Ken had grabbed her arms when she raised her fists in frustration. Another night, Mary left the house in a fury. Neighbors took me to see Forty Pounds of Trouble while Ken searched for her. I heard a familiar hacking cough and instantly knew she had taken refuge in a movie theater, a characteristic she certainly passed along to me, along with an only child’s best friend: a love for reading.

|

| Heidelberg (April 1964) |

Gradually, Mary’s health and mood stabilized. She made friends with Eleanor, a lovely British housewife who lived across the hall, ending an isolation that had begun with her arrival in France more than a year earlier. She persuaded Ken to get me another dog, a poodle with a pedigree she named Charlie, after DeGaulle, the French president both she and Ken despised for his Gallic air of superiority. We resumed our family travels and she and I began going to movies together now that I was too old for the kiddie fare that previously had been Ken’s domain. Dr. Strangelove was OK, Psycho wasn’t.

|

| London, 1964 |

If I had to pick my happiest memory of Mary, it would be the afternoon we saw both

Bonnie and Clyde and

The Graduate in two of downtown El Paso’s commercial-run theaters, one an old-fashioned movie palace complete with stars on both the ceiling and the screen. To save money, we usually waited until movies played at Fort Bliss for thirty-five cents or at the drive-in, months after they were released. Mary also took me and two sisters who lived across the street to see

Valley of the Dolls, discreetly sitting separately from us with her own friend after purchasing our tickets. “Mrs. Hon, you’re the coolest mother ever,” they gushed. Mary's coolness factor increased exponentially several years later when she scored

Rolling Stones tickets for the three of us in Albuquerque while in town to see a cancer specialist.

|

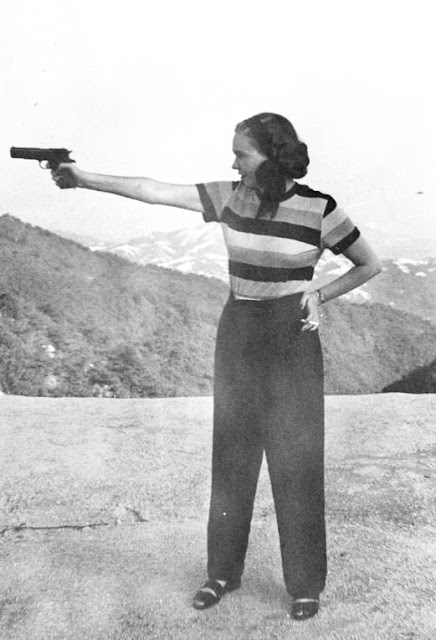

| Charlie & Mary in Cloudcroft, New Mexico (1966) |

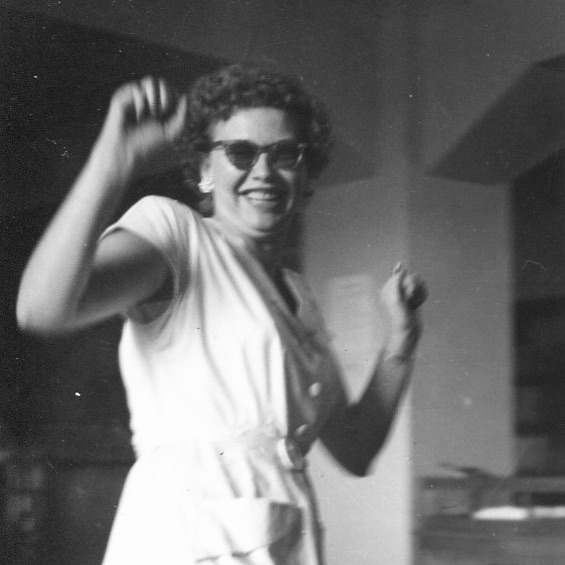

The Ostrander women were vain, no question about it. Neither EVER appeared in public without being dressed to kill. Mary’s hair color changed numerous times in her final years—and there were wigs after the chemotherapy she endured for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—but more and more she preferred the comfort of a hot pink robe. I would find her stretched out on the couch when I returned home from school or, on her good days, sitting on the kitchen stool under the yellow Princess telephone, giggling with Laura, her El Paso bestie another Army wife who valued her sympathetic ear coupled with unflinching candor.

|

| Christmas with Laura & Susan Payne, & Charlie (1967) |

|

| December 1967 |

“How are you feeling, today?” I asked, ritually. “Fine,” she typically demurred, but I knew better after sneaking a peek in her medicine cabinet in the bathroom where I showered: row after row of translucent plastic pill bottles filled with Darvon, the same color as her robe. Pain, and probably depression, had stranded her in her own valley of the dolls.

Ken figured he could avoid another tour of duty in Europe before retiring if he volunteered to go to

Viet Nam for a much briefer period in a war zone. Mary hated the idea but relented in the face of its logic and her desire to stay put while I completed high school. Prior to his departure, Ken dutifully gave me the man of the house speech. Without a driver’s license, I couldn’t help Mary much although I did the lawn work and kept her company. She put on her best face after being left alone to handle a hormonal teenage son while facing down a cancer diagnosis.

We certainly had our share of “Mom, you’re embarrassing me” moments, nearly all of which were caused by her propensity to say exactly what she thought. As a group of neighborhood kids watched me struggle to replace the sprinkler heads that kept popping out of the watering system Ken had installed, she yelled “Instead of standing there like a bunch of idiots, you could offer to help him!” They scattered in fear. And more seriously: the wind blew so hard in the spring that Mary occasionally would pick up me and my friends after school, a long walk away from home. As two of us took refuge in the Rambler from the sand waiting for a third, an older girl sashayed past, pressing her books to her lowcut blouse, her dyed hair, as long and straight as any hippie’s, hanging down to the bottom of her miniskirt. “Get a load of that tramp,” Mary observed unkindly but not inaccurately by the comportment standards of her generation. “Uh, that’s my sister, Mrs. Hon” replied Ronnie from the back seat. “I’m sorry Ronnie, I didn’t know,” she answered no doubt as mortified as I.

|

| Christmas 1967 |

Ken’s absence coincided with my sexual awakening. Fortunately, Mary’s bookshelves—lined with Literary Guild selections and best sellers by Harold Robbins, Jacqueline Susann (“nobody can write a dirtier book than a woman,” she averred), James Jones and Henry Sutton (The Exhibitionist introduced me to blow jobs)—educated her horny teenager. She hid only Portnoy’s Complaint (in her lingerie drawer!) perhaps because my semen-encrusted sheets suggested I was already masturbating quite enough, thank you very much. And despite the prudishness Mary displayed regarding Ronnie’s sister, she probably was the only mother on Collette Street who had an impressionistic paint-by-numbers canvas of a nude woman hanging in the master bedroom. At least that’s what the other kids claimed when I gave them a tour.

Mary loved her magazines, too. Life and Look and especially Time connected her to the world beyond El Paso where everything seemed so second-hand. I also looked forward to her return from the beauty parlor for oral dispatches from movie magazines that would add no middlebrow veneer to her coffee table.

Even before Ken left for Saigon, where he insisted he would be out of harm’s way, dinnertime—usually of The Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook variety—coincided with the “living room war.” But Mary abruptly lost her stoic composure the night Walter Cronkite reported the Tet Offensive in 1968, seven months into Ken’s mostly uneventful tour. Friends and neighbors gathered with us for the next couple of days until Ken got word to Mary that he was okay.

It’s funny what sticks with you: what I remember most vividly about that family trauma is the aftershock. “How can I watch soap operas when Ken could be killed at any moment?” Mary answered when I asked why she had stopped following the drawn-out shenanigans in Oakdale.

|

| June 1968 |

So much of parental life is hidden from children. Not until I found a couple of Mary’s typewritten letters to Ken—they wrote to each other almost daily for thirteen months—did I understand how completely stressed she must have been but also how cognizant she was of the impact Ken’s absence was having on me.

Jeff thought you had probably received the news about Cratchit but I assured him you hadn’t. He was anxious to see what you wrote about the incident. Now he tells me he wants only one thing for his birthday and that’s another guinea pig so I’m afraid we’re in for another occupant of the house. I really don’t mind and I think he feels halfway guilty because he let it out in the open where it could be killed.

|

| Letter to Ken (June 29, 1968) |

Memory transformed the “news about Cratchit” into the most important life lesson Mary ever taught me. Ken and I had built my beloved albino guinea pig a hutch but on warm days I let him have the run of the fenced back yard. Both Mary and I thought it was hilarious when Cratchit came to the screen door demanding lettuce with a loud “wheet, wheet.” But one afternoon, when I returned from school, Mary looked stricken when she instructed me to take a look in her tomato patch where I found Cratchit, the bloody victim of a cat. Mary didn’t try to protect me from the realities of life—or the consequences of my actions—that’s for sure. “Face the music” could have been her motto.

Nor will I ever forget the summer after we returned from Heidelberg when I pleaded for a membership at the Crystal Pool. I hoped to spend afternoons there with my best friend from Milagro Hills. Swimming at the aquatic facilities on Fort Bliss cost nothing so Mary resisted until I promised I would bike there every day, relieving her of the transportation burden and fuel costs. She made me stick to my promise even though Mike, who had matured into a sexy juvenile delinquent, wanted nothing to do with me, a geeky kid with glasses & braces (Mary’s first cosmetic intervention, quickly followed by contact lenses). Despite an occasional splurge, money in Mary’s house “didn’t grow on trees,” a value so successfully embedded that I was able to retire comfortably with plenty of savings, even after a career in non-profit.

Mary passed on more abusive features of her personality as well, foremost among them “the silent treatment.” Mary never struck me and rarely yelled but I greatly feared offending her. When Ken and I forgot her 50th birthday, she didn’t speak to us for days. Another time, when I described going on a weekend ski trip, she teased me about being more interested in the “après ski” than the sport itself. “Since when do you speak French?” sneered the jerk whose French consisted mostly of “la souris” and “le crocodile.” Mary showed affection through active listening, so to have her withdraw it caused acute psychological distress in both her husband and son. You knew when she was pissed, that’s for sure.

It wasn’t until I went away to college (“for a nickel, I’d take him right back home” cried Mary—literally—on dreary West 114th Street when she and Ken dropped me off at Columbia in 1971) that I reaped the dividends of her listening skills. Reading her chatty letters, which sounded like eavesdropping on one of the gossipy conversations she had over our stone wall with Mrs. Day, a much younger busybody, helped me overcome my homesickness, although the updates on post-high school life from friends who dropped by to see her did not.

|

| 1971 |

The summer after my sophomore year, my last in El Paso, I picked up Tom, my former roommate, in Tucson after a fencing competition. During a tour of my hometown we got high as kites with a couple of young women who’d also smoked marijuana together for the first time after going away to college. When Tom and I returned to our house afterward, I went into my parents’ bedroom to say goodnight to Mary, who was watching Johnny Carson, as usual. By this time, Ken had retired from the Army and was working for the federal Drug Enforcement Administration. “Well, they thought they were going after a ton but they came back with a roach,” Mary recounted as Ken snored beside her. It was beyond comprehensible to me, especially while stoned, that Mary could be so au courant with slang like this. It was beyond comprehensible to Tom that the same someone would make him pancakes when he arose at 11 a.m. the next day, long after I had left for my summer job.

Mary’s passion for Johnny Carson shoved me a little closer to gay culture, too. She called out one night as I returned from the late shift at Baskin Robbins/31 Flavors. “Jeff, come in here, you’ve got to see this woman.” While Bette Midler did her schtick, we shrieked so loudly with laughter that Ken awakened. “What’s so funny?” he demanded. “Never mind,” said Mary. “Go back to sleep.”

|

| Final Mother & Son Photo (Las Cruces, NM, 1973) |

Now that I think of it, Mary gave me another push toward diva worship around the same time when she suggested we catch The Owl and the Pussycat on Fort Bliss. Mary loved a good torch singer—especially Eydie Gorme belting “If He Walked Into My Life” and “What Did I Have (That I Don’t Have Now)” while she vacuumed—and news of Barbra Streisand’s incredible talent had permeated the nation’s cultural crotch. Both of us laughed helplessly at Barbra’s Brooklyn accent, her timing and especially her Yiddish.

If these memories seem mundane, it’s because so few remain, especially ones that are colored by pure joy. Mary’s letters tapered off as her cancer treatment weakened her. Neither Ken nor I wanted to believe that she might actually die, although there was no denying the reality of what was coming during the first semester of my senior year. Recently, I retrieved Ken’s letters from that period (the Hon men are archivists at heart) for the first time. They felt like reading the notes from a scientist observing a laboratory animal undergoing brutal, experimental and ineffective treatment.

|

| Mary & Her Mother Shortly after the Death of Her Father (July 1974) |

I made it back to El Paso just in time to say goodbye to Mary in February 1975. Although life-support equipment prevented her from speaking, she stroked my head as I rested it on her stomach, sobbing. “I love you, Mom” I said. “I only wish I’d said it more.” I’m not sure I ever had said it since becoming a teenager. We weren’t that kind of family.

For many years after Mary’s death I was relieved to have been spared the trauma of coming out to her. A mother always knows, of course, but I can’t be sure how she might have reacted especially because of an incident not long after we returned to El Paso for the second time. She had listened in on a phone conversation I was having with a new friend after Mike had dropped me. “I don’t want you seeing him anymore,” she ruled flatly. While I can’t exactly remember her justification, it had something to do with “real boys” not using the word “grand.” To employ Mary’s lifelong fondness for the current vernacular: WTF?

I once thought that losing my mother at the age of 21 wasn’t THAT bad. After all, hadn’t Mary been around for all of my childhood? And the loss has faded with time, along with the growing realization that caring for an aging parent can be one of adulthood’s most fraught responsibilities.

But I do remember how much I regretted her not being able to see my first apartment. Or to tell her about the night I saw Bette in “Clams of the Half Shell” on Broadway. Or that I understood why “Casablanca” was her favorite movie.

At least we’ll always have Paris.

|

| Ft. Bliss National Cemetery (2021) |

More Mary:

No comments:

Post a Comment